I felt conflicted because there was a gulf between what I thought I should feel and what I was actually feeling. I should be grateful, I told myself, that I was a perfect match. It would significantly increase the chances that my brother’s body would not reject my life-giving cells. And I was grateful, but another part of me wished I had not been so perfect.

I was afraid that I’d be a failure. That in fact my stem cells would be “bad blood.” I feared they would not be strong enough to do the job and that my brother’s life would not be saved. I feared that even if I gave everything I had to give, it would not be good enough.

My husband, who researched the side effects of being a donor, told me that a tiny, tiny, tiny percentage of donors had an allergic reaction to the shots they give to send stem-cell production into overdrive. I kept my husband awake the whole night after the first shot to make sure he didn’t miss the warning signs of collapse and imminent death. Tiny was too big for me.

I wanted to shout, “I’m scared!” to the many, many people who told me things like, “Isn’t it wonderful that you can save your brother?” or “God has given you the gift to do this. What a blessing!” or “You must feel so happy to be able to do this!” But I adopted the shy-smile-and-slight-nod approach, hoping it came across as warm acknowledgement and not the frozen sense of shame, duplicity, and angst that I really felt.

My brother and sister-in-law were so relieved when my “perfect” test results came through. It was a lifeline of hope. How could I do anything else but smile and confirm their positive feelings? I could see the fear and hope burning brightly in their eyes. They needed me to be their bright light, not a flickering flame.

I felt confused when I met a young medical student who was donating anonymously for anyone who might need her stem cells in the future. “Are you scared?” I asked her. “Why are you doing this?” I peppered her with questions, yet her answer was always some version of “To help others.”

I met a man who was in remission, donating stem cells for the time when maybe his transplant would have to be repeated. In this way he wouldn’t have to rely on another donor. I never asked my brother if he felt bad about my having to go through such a long process, and he never volunteered any thoughts to me about this. I felt guilty for thinking he should have.

It would have been nice if someone had said to me, “This must be hard on you,” or “It must take a lot out of you to drop everything and come here,” or “The loss of income must be quite costly to you having to find substitutes and pay all these expenses.” Money…another elephant in the room not to talk about.

I’ve practiced Zen for over forty-five years. In Zen, the image of the bodhisattva is a central teaching and a deep aspiration. A model of compassion, the bodhisattva dedicates herself to freeing all beings. Rather than entering nirvana, she chooses to remain behind until every last sentient being is also free.

In Zen, there are many stories about how the bodhisattva Kanzeon intervenes to serve and protect people. However, there’s a twist: She appears in whatever form is most helpful, and that’s not always what we think we need. So, receiving Kanzeon’s help might sometimes bring to mind the wise advice: “Be careful what you wish for.” My teacher would put it this way: “You don’t always get what you want. But you do get what you need.”

I began this article wanting to talk about the need for people to be more understanding of my situation. Could people quit projecting their aspirations onto me and stop emphasizing the positive and ignoring the negative? Could people acknowledge the messiness of my fear, practice generosity, and not be so damn naive and one-sided? I wanted to say, “Please, bear witness!”

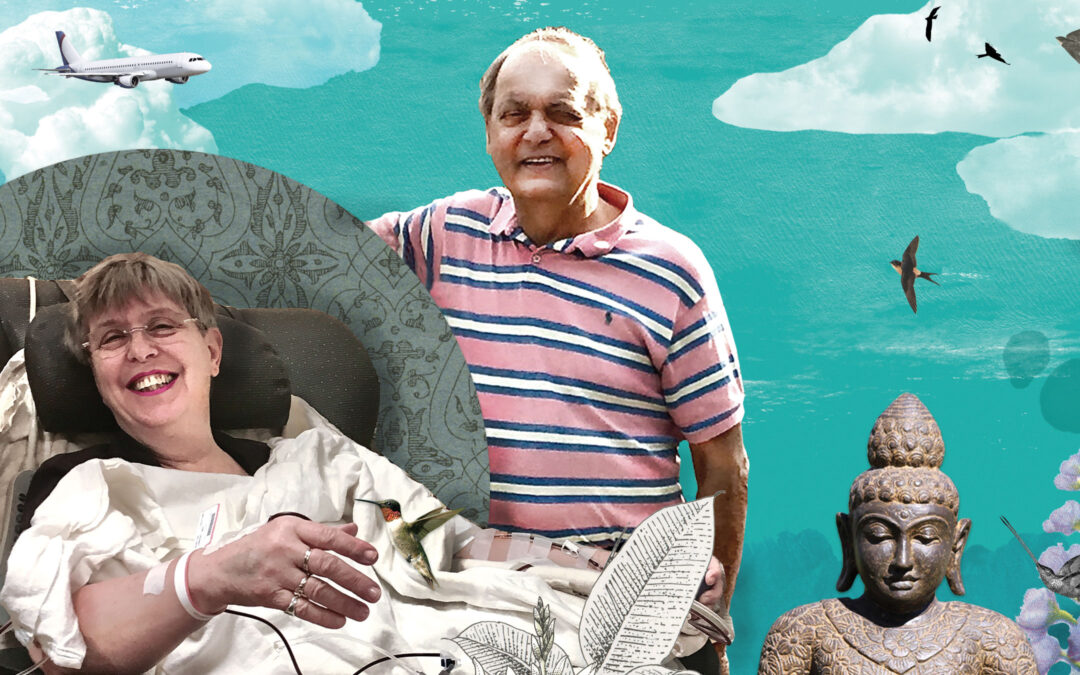

Now, though, I see how much I’ve learned—and will continue to learn—when I turn the light inward and accept the lessons this highly charged situation presented to me. Giving is hard sometimes, and it was vital to attend to my feelings with as much kindness and understanding as I could muster. Whether it can be proved or not, during the five days of injections, my change of attitude from burdened to wanting to express my love for Bob—and kindness to myself—had an effect. According to the medical staff, my stem cell production rate went from disappointingly low to off-the-charts. This was even more surprising given my age at the time (sixty-eight).

Shoulds and should-nots create a charged field of self-recrimination, fear, and blame. Allowing myself to experience whatever was presenting itself was deeply healing. It allowed me to embrace whatever was there: fear, pride, bravery, worry, feeling honored I could serve. Perhaps most challenging was facing the fact that Bob died despite all my efforts and those of the many people who were involved in his treatment. He died before he could receive the transplant of my stem cells.

I received the news of his death at 2 a.m. in the arrival terminal of JFK airport after a hectic attempt by way of Toulouse and Casablanca to get back to Bob’s bedside in time before he passed. I fell to my knees and wailed loudly. My daughter Taya took me in her arms, and we cried together. She had arrived twenty minutes too late after driving nonstop from Cleveland to Manhattan.

I felt myself racing from hurt, disappointment, and wanting to blame someone. At the same time, I was experiencing feelings of softness. I realized that neither I nor anyone else could have controlled the outcome. I was not to blame. The airline was not to blame for cancelling my original flight. My sister-in-law was not to blame for waiting too long to call me. Bob was not to blame for not waiting for me to arrive. I did the best I could. We all did. And that was enough.

Taya and I stood up, held hands, and walked to a coffee shop that was still open. There was no need to rush now. “I´ll have a BLT,” I said, and she ordered a bagel. It seemed both normal and completely out of whack to sit and munch on our orders. We held hands, tears dropping onto our food, while Taya described Bob´s last moments as communicated by my sister-in-law. He died in the presence of his wife and two children, while his sister was at thirty thousand feet. Maybe we passed each other as we journeyed on in life and death.

The next day Taya and I went to my parents’ grave where Bob would be buried. He’d join the likes of Ayn Rand, Lou Gehrig, Tommy Dorsey, Soupy Sales, Danny Kaye, and Anne Bancroft—all buried at Kensico Cemetery in Westchester County. What a cohort! We pulled the weeds, planted flowers, and cleaned the gravestone. When I’d visited New York City in the past, Bob and I would drive to the cemetery and spend some time there. They were some of our most intimate moments, a gift after many years of estrangement. “Chalk and cheese” does not even come close to describing the differences between us. And yet I was the one chosen to give him the chance of life.

As I write this, I see Kanzeon smiling at me and raising her eyebrows as if to say, “You asked for someone to show up for you and show you compassion! And that’s exactly what you got.”

Foxy lady! Very tricky, indeed.

More tears, flowing in gratitude for her teaching.

The post The Reluctant Bodhisattva appeared first on Lion’s Roar.

Recent Comments