On a gorgeous late autumn day—blue skies sparkling and crisp—four other Westerners and I followed a staffer from the Private Office up a sloped road to a detached concrete building. He ushered us inside, into a formal parlor with an old British feel: lace doilies on the backs of overstuffed chairs, magazines spread on a Western-style coffee table, and a faint smell of camphor. I was so nervous I wasn’t able to read the magazine titles even though they were in English. We signed a guest ledger and filled out a visitor’s form as instructed, then settled in to wait.

The others in the group, none of whom I knew except Sophia, began fussing over khata scarves and small gifts that they’d brought. Waiting in the room as well were Tibetan artisans in handsome waistcoats holding wood carvings or applique scrolls in their laps, seeking to show the Dalai Lama their handiwork before their installation in the new summer palace in Ladakh; and pudgy Indian officials in Western business suits with pomaded hair, their wives beside them in pink and mango-colored saris laced with gold thread, the red Hindu dot smudged between their eyebrows. No one uttered a word. We had plenty of time, I thought. Things rarely ran on schedule in India. Waiting, it seemed to me, was a form of yoga here.

I could scarcely believe I—a garden variety backpacker, without status or title who’d just set foot in Asia for the first time a few months ago—was minutes away from meeting the spiritual leader revered all over Tibet as the living incarnation of Buddha himself. The figure Tibetans in earlier years had prostrated on hands and knees across mountain passes to reach. The extraordinary head of state who had guided his nation in the last thirty years through the most tumultuous period in its 2,500-year history with unshakable hope, courage, and grace. The man of peace who, after studying his works, I felt had the stature of Mahatma Gandhi or Jesus Christ.

After a few minutes, Secretary Tenzin Geyche came in and rounded us up; he led us out along an outdoor balcony a few paces, then back into the building through large double doors. We were going to another waiting room, I thought, falling in behind Sophia. But Tenzin suddenly stopped beside a grand presence in floor-length maroon robes. I glanced up. Oh, God, it was him! The Dalai Lama stood beaming at us in welcome. It was HIM! In the flesh!

Sophia was bowing from the waist, holding the white scarf draped across her palms and high over her head. I was next.

Oh my god! All my gifts were still in my bag! I jetted to the side, swung my backpack to the floor, and snatched out my khata scarf and gifts.

The secretary called out, his voice measured and ceremonial: “Miss Sophia Torres… from Bogotá, Colombia… South America.”

I hoisted my pack, tucked the Tibetan incense box under my left thumb, the San Francisco postcard under my right, and unfurled the silk scarf. Sophia floated off to a seating area. Tenzin glanced up from his cue card as His Holiness eyed me, still bumbling, with a broad grin.

Just in the nick of time, I spread the scarf across my palms and rose to my feet. He looked about six foot two, so much bigger than I’d expected. I took a breath and stepped forward.

“Miss…Canyon…Sam…”

Oh my god, what do I do?!

“…from San Francisco…”

Bow?

“…California.”

Shake his hand? Isn’t that too Western? Too disrespectful?

“…The…U…S…A.”

What showed the proper respect? What was protocol for meeting the Buddha?

I know! I’m supposed to prostrate three times! But the others were nipping at my heels—there was no time.

Tenzin nodded at me. It was the moment.

Without the slightest pretense the Dalai Lama took the scarf from me and shook my hand. He had a remarkably strong and warm grip. The broad grin never left his face.

“Miss…Victoria…Olsen…” Tenzin announced.

I floated to the sofa beside Sophia.

“…from Lancashire…Wales.”

I watched the Dalai Lama greet the others in our party with the same sense of presence. His manner calmed me; I found him physically striking. He was one of the largest Asians I’d seen in the East, with a large head, a big open moon face and elegant, expressive hands. He was towering, yet carried himself with uncommon lightness and ease.

Sunlight from windows along the two long side walls poured into the room, a soothing aloe green. At one end of the room hung vibrantly colored scrolls of Buddhist deities and an altar with a gold statue of Shakyamuni Buddha in a glass case. It looked like the one in the Jokhang Temple in Lhasa, the most prized piece of Buddhist statuary in all of Tibet. The statue in the Jokhang had been a gift to the Tibetan King from one of his two Buddhist wives who converted him—and eventually the whole country—to Buddhism.

His Holiness invited Sophia to speak. “Our center in Bogotá draws larger and larger crowds every Sunday…” she said. I could sense how nervous she was, hear the small chokes in her voice, feel the delicate hairs on her arm stand on end inches away from me. “…A growing number of Tibetan Buddhists in South America…”

His Holiness listened attentively as she asked him to visit Colombia. Yes, he agreed. He’d never been to South America. He would take her generous invitation into consideration. Tenzin sitting to his right jotted down a note.

When it was their turn to speak, a redheaded Australian man and pale British woman delved into the subject of blood donations. They were doctors at the local hospital.

“Dozens die unnecessarily for lack of blood. People are very afraid. They just need to be assured donating blood will not harm them,” she said.

“A public statement from your office, perhaps,” the fellow suggested. “They’ll listen to you.”

The hospital was losing lives because it was unable to build up a blood bank. Tibetans feared donating because in the early seventies the Chinese took their blood against their will to treat Chinese troops wounded in a border skirmish with India. Scores of Tibetans died from excessive blood loss. Many townspeople—refugees—remembered. His Holiness listened thoughtfully and said he would take the matter into consideration. Tenzin took a note.

A woman with an owl-like face spoke next. In a crisp British accent, she invited His Holiness to visit Wales.

“Actually,” he responded, “I have been to England before. A number of times…England…Scotland…”

Perturbation washed over her face. She shifted uneasily, her body and face hardening. The Dalai Lama looked startled, then puzzled. She straightened her spine, blinking and snorting, and spoke again with pointed conviction. “But you have never been to Wales!”

The Dalai Lama turned to the secretary. They exchanged words.

“Oh, mmmm,” he started again in English, facing back to her. “In-de-pen-dence movement. Yes?”

She wagged her head in agreement.

“Yes, I know!” he laughed, grasping the situation. Tibet and Wales both had independence movements.

“I know! Same same.” he laughed. “Okay, okay,” he replied to her invitation. “Thank you very much.”

He shifted his gaze and invited me to introduce myself.

“I have been traveling in China and Tibet for six months. I came to visit my roots—to travel and live in China for a year.”

“Oh, Overseas Chinese,” he nodded. “Do you speak Chinese?”

“A little Cantonese. A little Mandarin.”

He asked about the situation of ethnic minority groups in China, and whether there were many overseas Chinese traveling in the PRC.

“Where did you go in Tibet?”

“I stayed several weeks in Lhasa all total,” I answered. “I went to Yarbu Lhakhang…and to Samye….Then the other direction to Shigatse and Gyantse…”

I told him I trekked to Rongbuck Monastery at Everest. Describing the unfinished, rocky rough road we took half way to Nepal to start the trek, I couldn’t think of a simpler word for “corrugated.” I gave up and just jostled up and down, pantomiming the horrid long-haul bus experience. He roared merrily in a deep ringing baritone. This guy and I were gonna get along.

I explained that I also visited Amdo, his birthplace in the northeast, now part of another Chinese province.

“Did you like Tibet?” he asked, with a grin.

My mouth hung agape. I felt my chest squeeze and a blush of tears rise in my eyes. I was totally caught off guard. Not just the question threw me but also how unaffectedly he had asked it.

He awaited an answer, yet I couldn’t get my jaw to move. Nothing came out.

Tibet had moved me like nothing I’d ever encountered in my life. And for him—the man who represented the very heart of this rich ancient civilization, the leader so cherished that tens of thousands of his people spontaneously protected him with their bodies for days to avert his kidnapping—to be asking in perfect innocence if I liked his country flabbergasted me. The gifts Tibet had given me could not be put into words. Moments passed before I was aware he still awaited an answer.

“I loved Tibet,” I replied softly, looking squarely at his big moon face. “I liked it very much.”

He was quiet a long moment, his bare arms resting on the sides of his chair.

“I remember…the air there was so clean…so fresh…” he said, gazing off across the room. “And the rivers were sooo clear…”

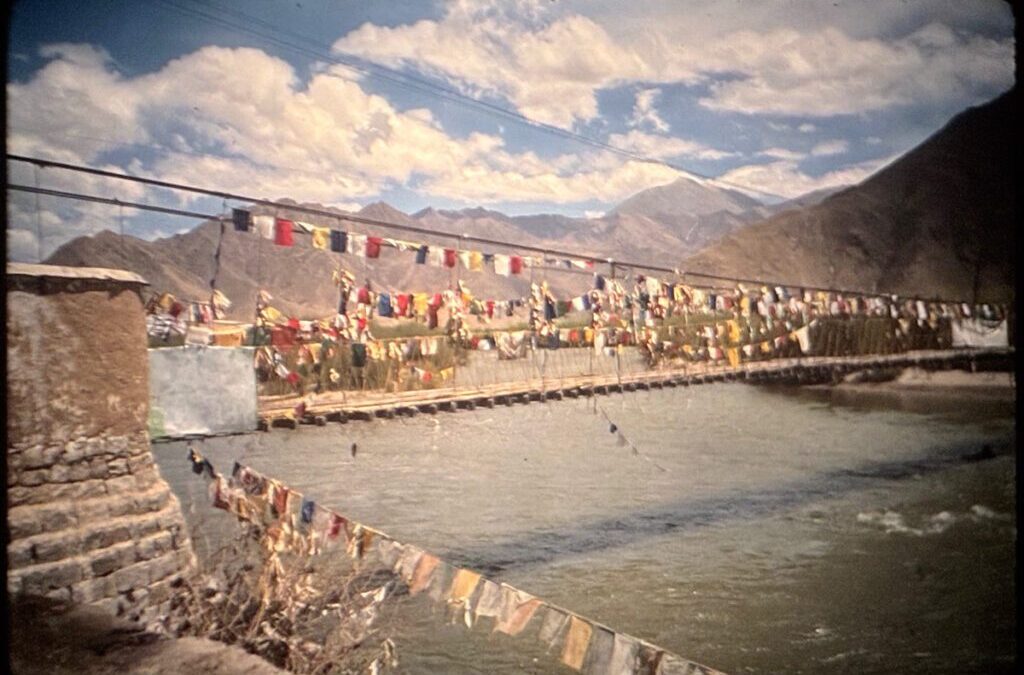

His mind seemed further and further away. I knew where it went. I knew those places. I could see the clear, raging waters of the mighty Yarlung Tsangpo, its unearthly, pristine beauty; hear the lapping currents of the river on Lhasa’s edge; walk again along the stretch of the Lingkor, the pilgrimage circuit skirting its riverbanks, to the summer palace; and see the bold line of the dust-colored hills rising on the opposite shore. All so wild and untouched. My mind flew to the wide-open valleys in the high plateaus—to the intensely vivid cobalt blue skies with their layer upon layer of curled clouds. I could smell the pungent, stinging scent of Himalayan air and see the sweep of snowcapped peaks stretching across the horizon.

“I wonder if this will change…in the years ahead?” he mused. There was no bitterness in his voice, no fear. His mind merely watched—as if seeing images cross a screen—and he was very, very quiet.

An immense sadness washed over me. So immense I could not bear to feel it all. The land of Tibet, experts say, will be an ecological and environmental catastrophe if China carries out its development plans there. Some of the most magnificent, unspoiled terrain in the world—the “altar of the earth”—would be irretrievably lost. Pillaged. Overrun.

“What questions do you have? Speak freely.” His manner was strong and commanding, but friendly

Sophia, on my left had saved money for ten years to fulfill her dream to come here and meet him. Now she sat at his elbow like she’d been hit by lightning. In a small voice she asked if it were true that when people achieved enlightenment they reincarnated only as men. I bristled.

The Dalai Lama turned toward Tenzin Geyche, asking something in Tibetan. He seemed to be checking his comprehension of the question. I waited with bated breath for his response.

He turned back to us.

“Oh, no. No!” he shot back in English.

“I didn’t think so,” I muttered softly. He heard me and burst out laughing, a wonderful robust laugh that rang through the room.

For my part, I’d been thinking hard about my one question. I had to find the one thing that I would most cherish his opinion on. This was my only chance to ask him, the living carrier of a highly refined philosophical and spiritual tradition that predated Christianity by five hundred years. After much reflection I decided there was no dharma question, save for one, that books, other teachers, or his transcripts could not answer.

Attachment—frustrated desire—was the source of all suffering, the Buddha taught; once we ceased grasping we had peace and happiness. I was returning to the States soon, the country where one was assaulted every minute to buy and spend, to crave and consume. The country where, a Thai friend said, she had no desire to live because people were free to be rich—but not free to be poor.

“How is it possible,” I asked aloud, “for a student of the dharma to live in the West, to practice freeing oneself of attachment, in a society that cultivates attachment? That promotes and rewards attachment?”

He nodded knowingly. “With the Buddhist mind, you understand the relative nature of reality. How any…um…condition…can be both good and bad…at the same time. Not just pleasant…eh…unpleasant, eh…but good, when it seems bad. And bad when it feels good.” His accent was similar to that of Indians, except phrases now and then carried the lilt and inflection of Tibetan.

“So, the relative nature of reality is a very, very important principle. Also altruism….that is…compassion, eh…patience, eh…tolerance. These qualities are very important.”

“In the West, a person who is loud, who is demanding…is called ‘strong.’ A person who is patient, who accepts circumstances…is considered weak. But actually, in Buddhism the person who can tolerate…who can accept conditions…is stronger. That person has more faith, more confidence. More balance. Less fear. The person who is intolerant, who is agitated….dissatisfied…they are weaker. In their hearts they have more fear…Less faith.”

He spoke about nonviolence, and then about pure motivation. Motivation precedes all action; therefore, the nature of one’s motivation determines the character and karmic imprint of actions.

He explained the necessity of aligning one’s actions with one’s mental attitudes: “The mind…the action…the speech…all together.”

His thoughts were so lucid, it was as if he were performing an exquisite kata—the individual form in martial arts—of the mind. Without my knowing when or how, somewhere along the line the boundaries dissolved. No longer was I the novice, the foreigner, barely keeping up with so many unfamiliar concepts. No longer did I hungrily seize on his words, try to understand them or store the ideas like a forest animal squirreling acorns for winter. I realized I was not on the outside anymore but instead had tumbled into another mindstream—his mindstream—and I was on the inside.

My consciousness felt like a silvery feather carried on a swollen, rushing river. The water sparkled—shimmering like crystal, like diamonds, catching reflections from every direction. It was luminous and powerful, yet utterly light. I felt my shoulders drop, my face sigh and come to a sweet place of repose, felt my mind let go and give in to the tide. I heard the words without anxiety; their meaning was of me and natural to me like the roar of the current. One moment I had been on the outside and then seamlessly I found myself on the inside. Being there…marveling in being there…reveling in being there. But mostly…just being.

At one point he paused and looked out. He seemed to be searching for a word, grasping for English vocabulary. The sunlight slashing in through the bank of windows lit his profile as he tilted his head to think.

“Peace,” he finally said, pulling the word down from the void. “Peace,” he uttered in a big, deep voice—rich and operatic, as if it could boom across a mountainside or in a concert hall.

“Altruism gives you this peace. If you have peace of mind…from loving-kindness…from not harming…from patience, then you can live anywhere, be any place, and you will have contentment. No upset. Peace.”

He was quiet a moment and thinking. He scratched his forehead.

“Mmmm,” he murmured. “Ah, yeh,” he intoned in conclusion. He looked at us again.

“More questions?” he smiled.

The post The Day I Met the Dalai Lama appeared first on Lion’s Roar.

Recent Comments