In Vigil, the character Jill lingers in the space after death, watching over a dying man. What were the influences that shaped the novel’s conception?

A lifelong obsession with death, mortality, and accountability. I was a zealous Catholic kid when growing up in Chicago, and it always seemed to me like preparation for a reckoning. For me, it wasn’t so much about heaven but the last minutes of life that seemed fraught. Will you be in a position to move on with composure, or in a state of terror?

A Christmas Carol was a big influence, but also, a couple of Tolstoy stories: “Master and Man” and “The Death of Ivan Ilyich.” Both are concerned with whether it’s possible for a person to subvert one’s habit energies and approach life in a truly different flavor. Another one by Katherine Anne Porter called “The Jilting of Granny Weatherall” is the same thing. There’s a woman on her deathbed who experienced trauma when she was younger and, all her life, had claimed she’d moved beyond it—we learn whether she did or not. That whole tradition is alive for me, both in a literary and spiritual sense: Are we just stuck in these mental habits, or can we change?

Why is the dying man in Vigil an oil tycoon?

I was noticing the weather, thinking of the people who, twenty years ago, were denying climate change. I wondered, almost like a joke, what would they say when they’re in a landslide or flood? Some must ignore it while others take it to heart and look at their own role.

I also have some background in the oil business. If I had made it some other profession, I might’ve been more inclined to demonize the person completely, but I could find corollaries within myself. When I was young and working in the oil fields, we justified and rationalized what we were doing—and glamorized it—so I thought that might come in handy. You don’t want to hate your main character, even if he’s really bad. Sometimes personal overlap lets you get some extra valences in there.

What questions about responsibility, legacy, or justice were you hoping to raise with this book?

Honestly, none. The thing I love about fiction is that it’s like traveling. If it’s a good trip, ideas you bring to it will be overturned. So, with a book like this, I’m aware he’s sort of the bad guy, but I want to find out more about him. If he’s done evil, what’s the nature of it? What’s his relation to it? Conveying a message is something I’m always fighting against. If I convey a message, I already know it, and the reader can feel I already know it; it’s just a lecture. So, the trick of craft is to get into material, get lost, have your initial assumptions overturned, and then you’re standing there in the rain with no idea which way to go. That’s the sacred space of writing for me.

Donald Barthelme said, “The writer is that person who, embarking upon a task, does not know what to do.” For me, that’s the similarity with spiritual practices. We’ve got all these conceptual ideas dominating our heads, which, as useful as they are, often lead us astray. They make us more certain than we should be. How do we get those ideas to quiet down so we can see what actually is? In fiction, you write a first draft full of those concepts and intentions. Then, in revising, those initial ideas get challenged and replaced by more interesting and more ambiguous ideas. Pretty soon you’re really off the path. You don’t exactly know what your book’s saying anymore, and that’s great. You can still work with it, but now it’s a text coming from somewhere other than your conscious mind. That’s very powerful.

But Vigil does speak to our cultural moment around climate and energy. What does it say about it?

I’m being a little evasive because Chekhov said a work of art doesn’t have to solve a problem, it just has to formulate it correctly. This was a book that I really enjoyed, because I feel like when I came out at the end of it, I was pretty true to that Chekhov idea.

I don’t want to read a book where somebody tells me climate change is real and bad. Anyone with any sense knows that already. When I was younger, I had more of the idea that the author should have a fixed view, and you should get it. Now, I don’t really have a fixed view, but I have the ability to present multiple views and then walk away from that table with everybody talking.

Your book Lincoln in the Bardo also explored the liminal space between life and death. How does Vigil continue or depart from that exploration?

They’re different because in Lincoln in the Bardo, the people didn’t know they were dead. The whole game for them was to break through to the understanding that life was done, and now it was time to get going and move on. They were also held there for different reasons; sometimes they were still in love with a living person, or felt like they’d been shortchanged, or whatever. And in that book, the way that world was made was that there was a next place. The idea was that they were supposed to get out of that graveyard and go up one floor.

In Vigil, they know they’re dead. Jill knows she’s dead, and the Frenchman knows he’s dead. And it’s a little less clear about what the next thing is for them. We only know that Jill isn’t ready to go on to that thing, and neither is the Frenchman. So, that was a slight change in their perspective. It was a pretty good joke the first time—you don’t know you’re dead—but I thought, well, what if you did know? Then it’s a whole different game.

Vigil deals with profound, difficult stuff, but it’s also playful and fun. How do you balance humor and gravity?

I mostly just try to keep the reader in mind. I conceptualize myself as an entertainer, meaning I have to keep you on the hook. I had a big breakthrough when I was younger, where I thought the person that I am in real life—who always could be funny and tried to make social things enjoyable—could be part of my writing persona as well. So, it’s a natural aversion to being too lofty. In my real life, if I want to tell somebody something I believe deeply, I’ll come in at a slant with joking and stories. I guess it’s a spoonful-of-sugar kind of idea.

How does your Buddhist practice influence the way you approach storytelling and character creation?

For me, it’s the other way around. Through writing, I was a Buddhist before I knew what it was. Somewhat early on I realized a textual moment is just like a real moment. When reading my story, how open am I to what’s actually happening on the page? If I have a bunch of ideas about why the book’s good, then I’m not that open to it—I’m denying evidence coming off the page. But if I can get my mind to quiet down a bit and concentrate on the sound of the sentence in front of me, it’s not “Is a sentence thematically important?” It’s just: “Do I like it? Does it sound good? Is it convincing me?” That early concentration was the first time I’d ever had a quiet mind. I wouldn’t say it was meditative exactly, but it was similar. So, later, when I started hearing about Buddhist ideas, I went, “That makes sense—that sounds familiar to me.”

Another way of saying it is that I first realized through writing that there was some other part of the mind than the everyday mind. I’d be working on a section, making small changes, and suddenly it would come to life. I was like, “Who did that? I didn’t—I’m the one who did the crappy first version.” It became exciting to think there was something I had reliable access to that was actually smarter, funnier, kinder, and all that. Then when I started sitting, I was like, “Oh, that’s similar.” So now, I trust that if I write by this method, it’s dharma, which is related to truth. How can you work with prose to make it less full of shit and more resonant and energetic?

What do you think the reader gets out of Vigil in terms of being with dying?

Whenever I read stories that are like the ones I listed at the beginning, I get a slight sense of urgency related to the fact that it’s going to happen to me, and then a feeling like, “Oh my god, I still have time to make changes, to try to prepare.” Spending 170 pages at the side of a dying guy certainly made me feel the preciousness of this moment in which I’m not dying.

Here’s what I hope. I love that somebody could feel tenderness for him alongside revulsion. If we say he’s a wicked former oil executive, that’s true. If we say he’s a doting father, that seems to be true. If we say he’s a pretty good husband who’s too much of a patriarch, that seems to be true. If we say he was a little kid who didn’t get what he wanted from his parents, that seems to be true as well. What makes it difficult is that we always want to choose one signifier. But with a novel, you get to have all of them laid on top of each other, and then the reader turns to me and goes, “What am I supposed to think of this guy?” And I’m like, “Exactly. What are you supposed to think about this guy?” It’s a slow-motion, mechanical form of training myself to think the way I’d like to think about people in real life.

Do you think that fiction ultimately helps us be more compassionate?

I think it does, especially if it’s good. Good fiction certainly has helped me. A lot of the ideas that prepared me to be a Buddhist, I got from Tolstoy and Chekhov. They’d take a person that I would normally rush past in the street, and they’d stop time and let me go into that person’s head.

I don’t know that it’s sufficient to overturn all the nastiness in the world. But for me, it’s a real touchstone—whether reading or writing fiction—to just go, well, actually, we can see a little more complexity than we do. And maybe we could train ourselves to slow down that first rush to judgment.

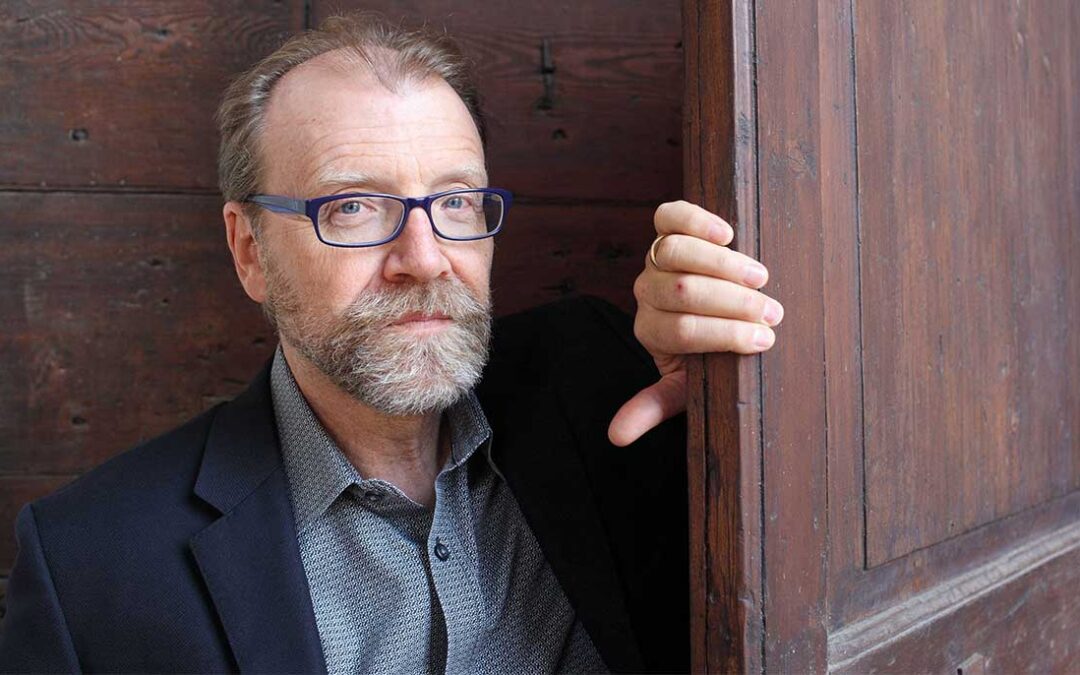

The post George Saunders on the Art of Not Knowing appeared first on Lion’s Roar.

Recent Comments