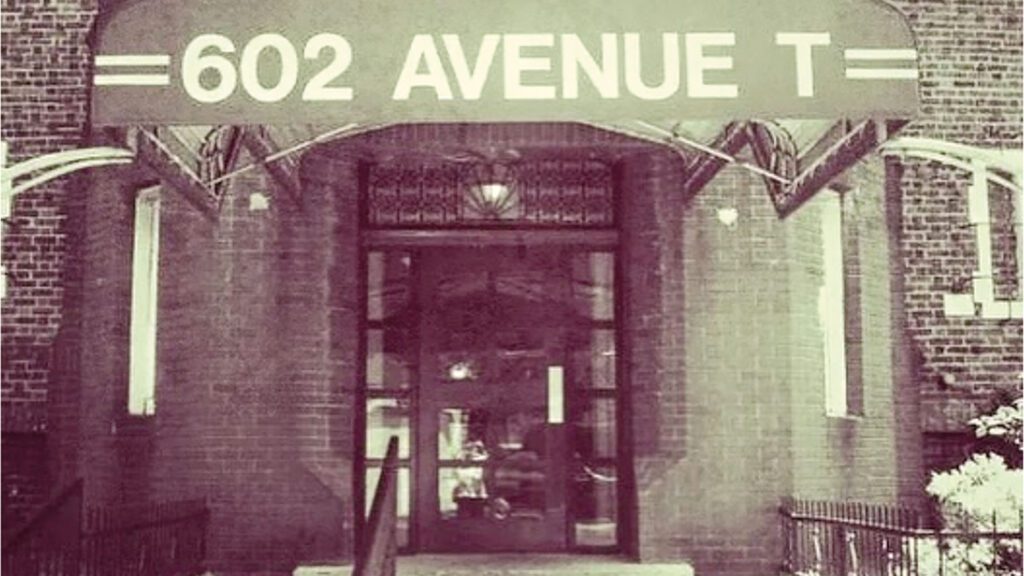

In 1991, shortly after my first serious breakup, I moved into my long-dead grandmother’s apartment near Coney Island. It was far from everything and everyone I knew—an hour and a half by subway from Greenwich Village. My father and aunt had decided to keep this apartment at 602 Avenue T just in case. They’d continued to pay the $142 monthly rent—which had gradually increased since they and my grandparents had taken up residence there in 1933—in case someone lost a home or got divorced, or the bottom fell out.

I pretty much hit all of those “just in cases” squarely on the head, and while I had once said that I’d never again cross the threshold, I had no choice: it was either move there or back into my mother’s apartment, and unless I wanted an eventual trip to the transplant list from sheer emotional trauma, it was going to have to be Brooklyn.

“Don’t make assumptions about what you can and cannot do.”

The day he moved me in, my father left me with two things: a one-liter bottle of Bombay Sapphire gin and a stern warning about turning on the oven. Don’t. It could explode.

Two years earlier, I’d been attending cooking school at night, working at Dean & DeLuca during the day, catering out of my tiny walk-up on weekends, and immersing myself in New York’s late-eighties food scene. It was a heady, contradictory time—a car crash of vertical plating and spun-sugar nests smashing into a rebirth of cucina povera. You could see it in my cookware department at Dean & DeLuca: kitchen tweezers and early sous-vide circulators alongside handmade French rolling pins; glossy black chargers the size of Pontiac steering wheels next to blue-and-white Cornishware; bird’s beak knives for carving radish roses beside old-school Sabatier chef’s knives that rusted if you looked at them wrong.

But by 1991, I had left professional food, gone back into publishing, and was living in the apartment that, according to my father, hadn’t changed much since 1933—and certainly not at all since I was a child spending Sunday afternoons there in the sixties and seventies. My go-to coping strategies were wrapped around cooking, but I couldn’t do that with an ancient oven that might explode. I couldn’t so much as make a meatloaf.

The shopping area where my grandmother used to buy kosher chickens, brisket, and challah was too far to walk, so I went in the other direction—to the Italian neighborhood on Avenue U, just two blocks away—and found both sides of the street lined with tiny, privately owned food shops: a salumeria, macelleria, formaggeria, alimentari. A fish store. A greengrocer. A wine shop.

Author Elissa Altman’s apartment building in Brooklyn, New York, in 1991. Photo by the author

The first time I shopped on that street, I was surrounded by a small army of tiny, black-clad, purse-lipped Italian grandmothers who glared at me, then asked, “What you gonna make with that?”—pointing to my basket that held a head of sprouting broccoli, a loaf of semolina bread, and one fig.

I stammered. They sighed.

I whined to the ladies about the apartment. I told them my father had warned me not to turn on my grandmother’s oven. They laughed. “You don’t need no oven,” they said. “You need to think like a baby, not like a robot.”

“Gimme a piece of paper and a pencil,” one of them said to the clerk. She scribbled a short list on brown butcher’s paper, handed it to me, and said, “Start here.” It read: olive oil, Parmigiana, porcini, garlic, butter, bread, sage, ricotta, egg, lasagna sheets. Then she rolled her eyes and stomped away.

I shopped on Avenue U every day for the next eighteen months, and I quickly learned what they meant by thinking like a baby: Come to everything with a beginner’s mind. It was a concept I’d later recognize as Zen.

The Japanese Zen monk Shunryu Suzuki (1904–1971) coined the phrase “Zen mind, beginner’s mind.” In his book of that name, he describes beginner’s mind as a state of openness, curiosity, and freedom from preconceptions. “In the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities,” he wrote, “but in the expert’s there are few.” The women on Avenue U didn’t quote Zen texts—yet they embodied its spirit with every stomp, sigh, and scribbled list.

The first meal I made for myself in my grandmother’s apartment—on top of the stove, using the list they had thrust into my hands—was porcini-stuffed ravioli with brown butter and sage. As I tucked into the meal, it was clear: Don’t make assumptions about what you can and cannot do. Treat every kitchen like a new space. Treat every onion like a new onion. Shop daily, buy what’s fresh, and cook it that night. See things new, every day.

Almost two years later, I moved out of my grandmother’s old apartment—my things packed up and the keys turned over to my father, who finally relinquished the lease after nearly sixty years.

Now, I look back over my life—at going to cooking school, and working at Dean & DeLuca, and editing cookbooks, and writing about food and nurturing and sustenance and hunger. I realize that in a sense I haven’t been writing about food at all. I’ve been writing about survival. About living.

And this has been the most important lesson I’ve come away with: Whether I’m engaged in food, or love, or finances, or finishing my next book, or aging, or spousing, or caregiving, or, or, or—beginner’s mind is the heart of it. It’s the beauty, the incredible discomfort, and the flailing, maddening truth of the gorgeous imperfection of humanity.

As I write this, we are close to the end of another summer, and the beginning of a new autumn. Inevitably, I will wake up on September first, and it will suddenly be fifty-nine degrees and the light will be different, and porcini will begin showing up in our local market. I may not feel ready to let go of the side of the swimming pool, but I’ll have to, because every September is a new season, and every onion is a new onion.

The post Every Onion Is a New Onion appeared first on Lion’s Roar.

Recent Comments